Generalissimo Franco and the Vatican

Generalissimo Franco and the Vatican

As a wartime ruler Franco got a modus vivendi — and only when his survival seemed assured was he dignified with a concordat. He gave the Church a religious monopoly and control of education and the press. In return, he secured the royal concordat privilege of choosing clerics, which helped him consolidate his grip on the country.

These are the arms of General Franco's Spain. The Fascist-looking eagle has a halo which sanctifies him as St. John. The royal trappings on this coat of arms are due to Franco's Succession Law. This declared that Spain was a monarchy (albeit without a king) and that Franco was a "regent", (rather than a "dictator"). This let Franco retain regal symbols like the crown — and also claim the concordat privilege of Spanish kings.

These are the arms of General Franco's Spain. The Fascist-looking eagle has a halo which sanctifies him as St. John. The royal trappings on this coat of arms are due to Franco's Succession Law. This declared that Spain was a monarchy (albeit without a king) and that Franco was a "regent", (rather than a "dictator"). This let Franco retain regal symbols like the crown — and also claim the concordat privilege of Spanish kings.

In 1941 Franco tried to reinstate the abrogated Concordat of 1851. He was hoping to assume the royal right to select bishops which was confirmed in this agreement. These patronage rights (patronato) would have allowed Franco to nominate a list of three candidates for a vacant see, leaving the pope to make the final decision.

At first Pius XII demurred. He replied that the 1851 Concordat was void due to its cancellation by the Second Republic. Further, he said, Franco was not a monarch, and the rights of a royal patron rested with the "Most Catholic Kings" of Spain.

However, a more plausible reason for the papal reticence was that the Vatican avoids wartime concordats. The Pope didn’t want to offer Franco the diplomatic success of a restoration, preferring to wait and make a permanent pact with him afterwards, when and if his regime survived the war.

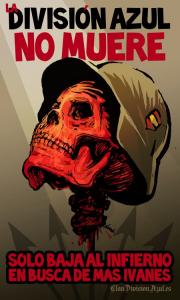

Although Spain was officially neutral, in June 1941 Franco arranged with Hitler for Spanish volunteers, the Blue (Azul) Division, to join German forces on the Eastern front to fight against Soviet Communism. [1] Two weeks later the Pope let Franco have a modus vivendi, to remain in force until a future concordat could be concluded. This provisional Convention of June 1941 gave Franco a limited version of the royal prerogative he sought. The Generalissimo was allowed to chose six candidates for a vacant see, the pope, if he approved, whittled these down to three, and then Franco made the final, face-saving choice.

Although Spain was officially neutral, in June 1941 Franco arranged with Hitler for Spanish volunteers, the Blue (Azul) Division, to join German forces on the Eastern front to fight against Soviet Communism. [1] Two weeks later the Pope let Franco have a modus vivendi, to remain in force until a future concordat could be concluded. This provisional Convention of June 1941 gave Franco a limited version of the royal prerogative he sought. The Generalissimo was allowed to chose six candidates for a vacant see, the pope, if he approved, whittled these down to three, and then Franco made the final, face-saving choice.

And the payoff for the Vatican? The 1941 Convention (in Art. 9) took over the first four articles of the 1851 Concordat, the ones that gave the Church a religious monopoly, as well as control of education and the press.

Finally, in 1953, when it was clear that this Fascist dictator was going to survive, Franco got a permanent agreement with the Vatican.

To the best of my knowledge Franco was the only leader to gain a patronato after the promulgation of the code of canon law in 1917. Not even Hitler or Mussolini achieved this in their concordats, and [they] played little to no role in the appointment of bishops. [...] In the negotiations for the 1953 Concordat the Vatican originally wished to take back [the limited] privileges [granted in the 1941 Modus vivendi]. That it did not was a testament to the many other gains made for the Church in the new Concordat. [2]

Franco's concordat gave state funding to the Church and legally enforced Church teaching. In return, the Vatican finally granted him the full version of "royal patronage" (patronato real). This was the ancient privilege of Spanish kings to name bishops and veto appointments down to the level of the parish priest.

This concession by the Vatican increased the control of a dictator who admitted cheerfully: "Our regime is based on bayonets and blood, not on hypocritical elections". [3]

When Franco reached his eighties, however, the Vatican employed its usual withdrawal of support for a dictator whose days were numbered. It had also used this tactic on another cocnordat partner, Baby Doc Duvalier, just before he was forced to flee Haiti. The Church began to distance itself from the aging dictator and reposition itself for the advent of democracy. In the name of church-state separation (!) the Vatican tried without success to get Franco to give up his long-awaited and highly- coveted right to appoint bishops.

At the Episcopal Conference convened in 1973, the bishops demanded the separation of church and state, and they called for a revision of the 1953 Concordat. Subsequent negotiations for such a revision broke down because Franco refused to relinquish the power to veto Vatican appointments. Until his death, Franco never understood the opposition of the church. No other Spanish ruler had enacted measures so favourable to the church as Franco, and he complained bitterly about what he considered to be its ingratitude. [4]

Notes

1. In addition to the Spanish Azul (Blue) Division, many other brigades were sent officially or as volunteers by rightwing governments to join Hitler's push against the Soviets:

Spain: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blue_Division (Its poster is below.)

Italy: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Italian_Army_in_Russia

Belgium: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/28th_SS_Volunteer_Grenadier_Division_Wallonien

France: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/L%C3%A9gion_des_Volontaires_Fran%C3%A7ais

Slovakia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Field_Army_Bernol%C3%A1k

Croatia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/IX_Waffen_Mountain_Corps_of_the_SS_(Croatian)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/13th_Waffen_Mountain_Division_of_the_SS_Handschar_(1st_Croatian)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/23rd_Waffen_Mountain_Division_of_the_SS_Kama_(2nd_Croatian)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/369th_Reinforced_Croatian_Infantry_Regiment

2. Zachary Wareham to Muriel Fraser, email, 1 September 2007.

3. Zachary Charles Wareham, The Cold War and the Spanish Concordat of 1953, University of New Brunswick, Department of History, 2007, pp. 10-12.

4. Jo Ann Browning Seeley, "Roman Catholic Church and Politics", Spain, Library of Congress Country Studies,1988, Chapter 4,/ Politics / Political interest groups / Roman Catholic Church. http://lcweb2.loc.gov/frd/cs/estoc.html

See also the review of The Spanish Holocaust: Inquisition and Extermination in Twentieth-Century Spain by the eminent historian Paul Preston in the New York Times, 11 May 2012.

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/05/13/books/review/the-spanish-holocaust-by-paul-preston.html