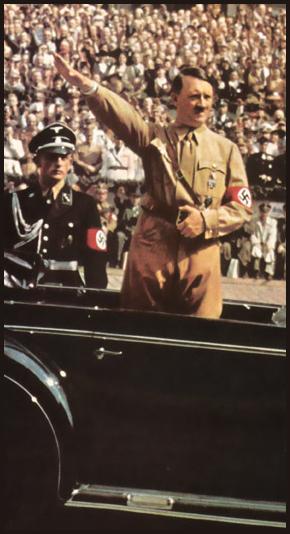

The German churches before and after 1945

A strategic alliance between Hitler and the churches was sealed by the 1933 concordat. Overriding their differences were their shared antisemitism and common respect for authority. This work by Professor Johann Neumann, an authority on the German churches, is available in English for the first time.

The German Protestant churches, not having concordats, didn't

enter any with Hitler, but they, too, compromised themselves.

This carving is on the pulpit of the Martin Luther Memorial Church

in Berlin. It shows Jesus beside a helmeted Wehrmacht soldier.

(On the other side is that a hostile Jew clutching his own sacred book?)

The walls were originally decorated with swastikas, but they have

been scraped away because the Nazi symbol is now illegal in

Germany. The church bells were also embossed with swastikas, but

in 1942 they were melted down to make guns and ammunition.

1. The background

National Socialism was no "accident" that happened to Germany, no unexpected event that overtook the German people and the continent of Europe and certainly no catastrophe that loomed suddenly before the Christian churches. Rather it was the consequence of German political and theological traditions.

The Nazis are only explicable in terms of a religious mysticism which incorporated the nationalism and racism that was current in Central Europe at the time. These diffuse movements included Pilduski in Poland, Primo di Rivero and later Franco in Spain, Mussolini's fascism in Italy, the militant Action Française in France, the Austrian fascism of Dollfuss, the fascism of Pavelic's Ustacha regime in Croatia and the National Socialism of Adolf Hitler and Alfred Rosenberg. All these were nourished by the same murky brew of racism, mysticism, nationalism, greed for power, belief in hierarchy and totalitarian utopia.

Although at the time of the First World War Germany was religiously divided, church leaders, both Protestantism and Catholic, were in agreement that their rulers enjoyed Divine favour.

A pastoral letter from 1.11.1917 by the Catholic bishops of what was then the Kaiser's Germany makes this abundantly clear. Here the bishops rejected the idea of the sovereignty of the people and the "buzzword about equal rights for all social classes". Despite the hopeless military position they also took a stand against a capitulation, "as the reward of Judas for breaking the oath of allegiance and betraying the Kaiser" for God had "through His grace placed the sceptre into the hands of our rulers".

The obviously impending defeat was merely the occasion for the bishops to call upon the Germans to redouble their efforts, and did not prompt them to even consider the possibility of bringing the slaughter to an end. Instead they affirmed that the Catholics would reject everything that would amount to an attack on the ruling houses and the monarchy. In the name of the faithful they offered the assurance that "We will always be prepared to protect not only the altar, but also the throne against internal and external enemies and the forces of revolution".

As the situation became even more desperate and it was clear that ever wider circles in the population were longing for peace, the state authorities asked the Protestant and Catholic clergy to help them contain the spread of "pessimism". The church hierarchies replied that they regarded this as their "self-evident national duty" so that everywhere the willingness to fight "will be supported by words of authority from the chancel". The bellicose war sermons and pastoral letters of this period are well known.

Nor were the German churches the only ones to encourage war in order to maintain the status quo. The French Church supported the French state in this regard and the Italian Church did the same for the Italian monarchy. The willingness to go to war wasn't specific to any nation, any faith or any class. Even the pacifist Workers International had collapsed in the face of the universal enthusiasm for war at the start of the First World War. Now the churches attempt to excuse themselves by claiming that they were merely following the spirit of the times: after all, everyone else was thinking, talking and writing in the same fashion. Unfortunately this is true, but this only goes to show that the churches possess no greater wisdom than others – let alone Divine Wisdom. They are just as fallible as anyone else, despite their claims to Eternal Wisdom, and these pretensions give them great power to lead people astray.

The increasing desperation brought on by the war finally made the workers and the trade union leaders once again - cautiously - advocate peace. However, still not the leaders of the churches. In fact, the clergy chose the wartime emergency to advance their own interests. The Catholic bishops - and the Protestants ones in a similar fashion - demanded that the government "clamp down on the decadent art and literature" that "toys with and mocks in a socially dangerous manner what is the primary source and strength of the state...." Above all, the bishops claimed, it was the duty of the state to require that the religious instruction of the children, the "natural right of the parents" to sectarian schools supported by the state (!) should be extended from the primary schools to the secondary schools and the universities. In other words, the churches wanted to use the military and political emergency to increase their own influence and to stifle any opposition to this plan. The churches had been called upon by the state to use their authority to lend support to the government, and now they demanded that the state use its powers to secure their position.

In the end, however, even this symbiotic co-operation didn’t manage to delay the end of the German monarchy. It is a bit disturbing to read the first pastoral letter of the German bishops after the end of the war (22.8.1919). Their main regrets concerned the introduction of the "religion-free, godless primary schools" which were supposed to be the beginning of a cultural struggle which would seal the fate of the German people. This prognosis inspired the dramatic title of the whole pastoral letter: "Under threat of death"". Only brief mention was made of the millions of unnecessary victims - the cripples, widows and orphans - and even this was done as if the churches had had nothing to do with the matter and, indeed, as if their warnings had been ignored. On the other hand, the bishops announced that the separation of church and state would set the stage for the destruction of Germany. Though they might not be touched by the human misery all around them, they were deeply troubled that the separation of church and state could lead to the loss of church property and the end of state subvention.

The Catholic schools mentioned in this pastoral letter of 1919, together with the topic of Christian marriage, would remain the chief themes of episcopal utterances and the focus of Church political activities right on into the 1960's....

According to the bishops, the democratic notions of the freedom and equality of all men and all classes, together with the right of free expression of opinion posed a grave threat not only to the Catholic Church, but also to the population as a the whole (23.10.1922). Accordingly they branded the democratic revolution as "the hour of the powers of darkness". From that point onwards, with increasing boldness, vice had unfurled its "shameful banners" and besmirched the "pure morals, the sacrament of marriage and the sacredness of the family".

2. The relationship of the churches to the Weimar Republic

The democratic revolution also shook the Protestant churches by removing the princes who had functioned as their heads and, as a result, they were at first too busy with their own affairs to comment on the new republic. However, from the outset the Roman Curia and the Catholic bishops offered the young republic neither co-operation nor good will. In fact, they didn’t even show the respect for state authority that until then they had constantly admonished, and which - after the Nazis took power - they would admonish once again. For example, the request by the new government that they give favourable mention to the Constitution Day (11 August) was declined with the remark that "the unreasonable demand to be loyal to the present constitution" was not acceptable. And in 1921 Cardinal Faulhaber clearly rejected the young republic and its principle of the sovereignty of the people, when he said: "Kings by the grace of the people [are] no grace for the people", but rather "where the people are their own king ... they will sooner or later dig their own graves".

His rejection of the democratic form of government was even more clearly expressed at the Catholic Conference in Munich in 1922. There he said: "The revolution was an act of perjury and high treason, it will go down in history as genetically flawed and branded with the mark of Cain". True, Konrad Adenauer, at that time president of the Catholic Conference, noted in his concluding speech that "Catholics as a whole do not stand" behind this political judgement of the Archbishop of Munich. However, this didn't manage to negate the effect of the words of the influential cardinal on many Germans.

In the years before Hitler came to power, the German bishops also repeatedly condemned the Nazis, as well. However, this was because of their anti-church stance. The Nazis' contempt for the democratic constitution and human rights, their antisemitism and the brutality of their movement, all these didn't rate any mention by the bishops. When on 30.09.1930 the diocesan authorities of Mainz - not the Bishop of Mainz - took a firm stand against National Socialism and denied any member of this party admission to the sacrament, this clear, but blanket, ruling was considered by many bishops to be, in the words of the Bishop of Regensburg, "untenable, and even ... inopportune ..., tactically imprudent and practically unfeasible".

After the elections of 14.9.1930, when the Nazi party with 107 representatives became the second largest fraction in the German parliament, quite a few bishops began to reconsider their position. They believed it would be better to adopt a gentler tone towards the Nazis, who now constantly stressed their positive attitude towards Christianity and seemed to seek an amicable arrangement. It didn't hurt, too, that the Nazis had "inscribed on their banners a war against godless Marxism".

In view of these softer tones, a young Catholic publisher called Walter Dirks made an unusual and prophetic analysis - and this as early as 1931.

Although Catholicism certainly has no sympathy with the Cult of Wotan or the Deutschkirche, [a movement in German Protestantism which wanted to purge "Jewish" elements from "Arian" Christianity], it still has sympathy with some of the less crude forms of fascist ideology. Terms like "authority", "faith in the Führer" and "law and order" find appreciation there. It's a short road from the economic program of the NSDAP [Nazi party] to the "solidarity", the "class society" and similar notions that are widespread in Catholicism. The Nazi front against "Liberalism and Materialism" overlaps to a certain extent with the corresponding Catholic battle lines, and they also share the Nazis' opposition to Marxism.

3. Shared interests and fateful manoeuvring

The infamous Ermächtigungsgesetz [Enabling Act] (24.3.1933) was a law passed by the German parliament by which it essentially abolished itself. With this parliament effectively turned Germany into a Nazi dictatorship. Only a few days later the Catholic bishops issued a statement which can only be understood in terms of the inner affinities noted by the young publisher quoted above. By this time Hitler had already had many opposition politicians arrested and others had found it advisable to go into hiding, yet in their declaration the bishops claimed "to be able to be confident that the general prohibitions and warnings need no longer be regarded as necessary". With this they sealed the loyalty of the Catholics to the new "legitimate authorities". The Protestant churches regarded the Nazis even more favourably. For example, in a confidential pastoral letter a church superintendant who was later vaunted as a member of the "church resistance" wrote in the same month, after the repression had begun, "There will be very few among us whose hearts do not rejoice at this [political] change". For many Catholics, as well, the election victory of the Nazis amounted, as a Catholic newspaper put it, to "confirmation that Hitler was in the right".

The church leaders shared with many of their contemporaries an overestimation of the Teutonic virtues which were supposed to be of such benefit to the world, and especially the tendency to authoritarian structures and military organisation.

What the bishops overlooked is that the freedom and rights of the churches were inseparable from the political freedom of everyone. They seem not to have noticed that Church youth groups and clubs can only flourish if all other organisations are free to exist. They seemed to assume — in fact, perhaps even to wish — that the Catholic Church would be able to exist in freedom, even when all other social groups, the Socialists and Liberals, the Jews and Freethinkers, were eliminated. They understood freedom only as "freedom for the Truths of the Church". The professor of church law, Josef Wenner, was not unusual in the way he greeted the "Emergency Measures Act of the President of the Reich for the Protection of the German People" (of 4.2.1933). This placed the country for practical purposes under martial law and allowed Hitler to arrest members of the opposition, including faithful Catholics. Yet he applauded it as an "energetic and purposeful measure of the government for national improvement" in the "struggle against the enemies of German culture and Christian morals".

The German bishops affirmed in their "Common Pastoral Letter of the prelates of the Dioceses of Germany on the Church in the new Reich" of 3.6.1933 that:

"In our Holy Catholic Church the significance and value of authority is shown to particular advantage.... It is therefore by no means difficult for us as Catholics to appreciate the strong new emphasis on authority in the German state and to readily submit, as we denote it not only as a natural virtue, but as a supernatural one, as well.... To our great joy, the leading men of the new state have explicitly stated that they base themselves and their work on a Christian fundament. This is a solemn, public commitment that has earned the heartfelt thanks of all Catholics".

By this point many of the Nazis' political opponents of all kinds had been beaten up, had disappeared or were in "preventative detention", and the first pogroms against the Jews and the Communists had already taken place. In other words, the bishops were in a position to know exactly what "the leading men of the German state" were capable of. According to them Jews, Gypsies, homosexuals, Socialists, Bolsheviks and "Liberal decadents" had no claim to humane treatment or to freedom and the protection of the law. In this matter the bishops and broad sections of Catholics, as well as the conservative Protestant Christians were in agreement with the Nazis. The bishops appear to have hoped that the Catholic Church could be strengthened by the destruction of her traditional opponents, because she was protected by the Reichskonkordat, a pact that the Pope had signed with Hitler.

This may help to explain the triumphant tone of the pastoral letter: "Never again shall faithlessness, and the immorality that this unchains, poison the marrow of the German people, never again shall the murderous Bolshevism with its hatred of God threaten and ravage German souls...." They closed their pastoral letter with the hope that "the prudence and energy of the German Führer [will succeed in] quenching all those various sparks and glowing brands that are intended to be fanned into fearful fires against the Catholic Church".

This attitude is particularly difficult to explain away, when one compares it with the bishops' brusque refusal of any support for the Weimar Republic, even though the Catholic Centre Party was continuously a part of that government.

In 1937 the Munich cathedral capitular and canon, Erwin Roderich Freiherr von Kienitz, wrote that the Catholics had finally recognised "the corrosive action on the Church of this democratic-parliamentary posture" - rather late, it is true - but recognised it nevertheless.

Indeed, the inner affinity of Christianity to totalitarian Nazism - both in its Roman Catholic and its Protestant forms - is quite startling.

4. Clues to the possible causes of the churches' behaviour

It was belief in authority, loyalty to the Kaiser, and the expectation of benefiting from an authoritarian government that made the church élites view the Nazis so favourably. Thus the Catholic theologian, Karl Adam, found "between nationalism and Catholicism no inner contradiction", but rather they belonged together "like the natural and the supernatural". On this basis he was able to conclude that "the Jew, as a Semite, is alien to the [German] race and will remain racially alien", and he even justified the "German demand for purity of blood" through "God's revelations in the Old Testament". In the face of the fact that "the specifically Jewish soul is infiltrating more and more our press and literature, science and art, indeed our whole public life, ... one must regard the actions of the German Government against the Jewish deluge ... as a dutiful act of German-Christian self defence". He continues: "So far as the overthrow of Jewish influence has struck the worldwide Communist-Bolshevik movement in its cleverest and most determined agents, this political antisemitism is doubtless in agreement with general Christian and ecclesiastical interests".

The Protestant New Testament scholar, Berndt Schaller, has investigated the precarious relationship between Christians and Jews during the Nazi period. He comes to the disturbing conclusion that although church circles clearly rejected the pogroms against the Jews in private, neither Catholic nor Protestant bishops and church leaders had spoken out against the violence in public. Only a few of them, like the Catholic provost, Bernhard Lichtenberg in Berlin and the Protestant pastors from Wurtemburg, Julius von Jan, Helmut Gollwitzer and a few others, actually talked about the persecution of the Jews and took a stand, either openly or in veiled terms. It is staggering to note that even in these critical remarks, antisemitism was in no way questioned, but was often explicitly affirmed. Apart from State Bishop Wurm who protested to the Federal Minister of Justice, most of the clerics of all churches and most of the church publications, as well, remained silent.

It is particularly shocking that the church leaders were silent, not due to fear but rather, as State Bishop Heinrich Rendtorff put it, "from considerations of principle". He explained these principles, as follows… "The Church is thankful that finally there is authority once more. That being the case, it would go against religious beliefs to thwart the temporal authority, especially since this is a central point of the government's programme". Where is the obedience to the word of God that the churches normally swear to uphold? Was the commandment, "Thou shalt not kill" no longer the word of God?

Worst of all was that those who did not remain silent about the brutal attacks on the Jews in the Reichskristallnacht in November 1938 often approved of the pogrom or even welcomed it. They were able to cite here — as did State Bishop Martin Sasse — the authority of Martin Luther. Sasse wrote:

"On the 10th of November, 1938, on Luther's birthday, the synagogues burned in Germany. ... This is the hour when the voice of the man must be heard - the German prophet of the 16th century — who out of naiveté began as a friend of the Jews but, prompted by his conscience, driven by experience and reality, became the major antisemite of his time and warned his people against the Jews".

In the first year of its publication Martin Luther and the Jews had a run of 150,000 copies.

Nor was it just members of the Deutschkirche, the Protestants, who wanted to purge "Jewish" elements from "Arian" Christianity, and regarded themselves as the "Storm Troops of Jesus Christ" who joined this chorus of the against the Jews. Even those who felt themselves bound by traditional Christianity also launched tirades of hate. After the November pogrom, the Deutsches Gemeinschaftsblatt of the mainline Lutheran Church published a "Word about the Events of the 8th-10th of November". There it says, among other things:

"The Jew is to be regarded as a 'terrible hater'. That lies in his particular nature ... ever since the time when he condemned Jesus Christ and brought him to the cross with a downright satanic hatred". After it had warned of the "eternal, malign and pernicious World Jewry" and of its "plan, followed with tenacity and great guile, for a more-or-less visible Jewish world domination", [it went on to assert:] "We find ourselves literally in a war with world Jewry. Only with this perception can we attain a clear and correct view of what is transpiring."

From this it was concluded:

"Wars must be waged with the means that hit the enemy the hardest, and even annihilate him. That is simply the fearful purpose of war.... But when the Jewish-democratic press of foreign countries act as if fearful cruelties have been practised by us, that is simply not true".... "The most vulnerable points for the Jew ... are his synagogues and his money. What money signifies to the Jew, everyone knows, but not what the synagogue means to him. This is not only a religious shrine, it is also a Jewish clubhouse where completely different things are done as non-Jews assume."

This hate-filled text from a church bulletin could just as well have stood in a Nazi propaganda sheet like Der Stürmer.

Several Protestant State churches even ruled that non-Aryans could no longer be ministered to, and that ministers who were not pure Aryans were to be removed from the service of the Church. In 1939 the pro-Nazi movement in the Protestant Deutschkirche issued the "Godesberger Declaration" which proclaimed that the Reformation of Martin Luther was being continued by the National Socialists. However, not only in the infamous Godesberger Declaration, but also in an announcement in the German Protestant Church bulletin of 6.4.1939, which was signed by eleven state churches, it is stated: "The Christian faith stands in irreconcilable opposition to Judaism".

The Protestant churches set about the "dejudification of Church and Christianity": Protestant pastors, deaconesses and parishioners of Jewish origin were all dropped like hot potatoes. As an institution, the Church denied them any solidarity.

Late, very late, however, other tones were heard. In October, 1943, the Breslau doctrinal synod finally declared that: "The annihilation of people, only because they ... are old or mentally ill or belong to a different race is not a state function which has been given to the rulers by God". And State Bishop Wurm, who before the war had announced in Nazi jargon that the Württemberg clergy was "Jew-free", now showed personal courage in denouncing before Hitler and the federal government the murder of the mentally ill and the Jews. That should be recognised, but such isolated examples do not serve to distinguish the church leaders from other, equally courageous critics of the reign of terror, who didn't happen to be Christian.

The Catholic poet, Reinhold Schneider, says of the Germany-wide pogrom of November 1938 in his postwar memoirs, Verhüllter Tag (Enshrouded Day): "On the day the synagogues were stormed the churches ought to have stood shoulder-to-shoulder with the synagogues. It is pivotal that this did not occur". As this verdict of a contemporary indicates, the Christian churches and parishes failed morally, both individually and collectively. It was only individual Christians — and individual non-Christians, as well — who dared to protest against injustice, tried to do something for the disenfranchised and oppressed Jews and attempted to help the persecuted Socialists and Liberals.

How is it that, as Bernd Schaller notes, "German Christianity and the German churches failed" so badly? Five factors seem to have played a role in this moral malfunction.

1. One factor was certainly fear, but that was hardly a decisive reason. Fear cannot explain everything because the Christian churches, especially the Catholic Church, had at its disposal relatively powerful, well organised parishes with wide social and political connections. It is true that the fate of many individual Christians, such as Pastor Julius von Jan and Cathedral Provost, Lichtenburg, showed that it was a dangerous game to oppose the new authorities in their drive to restore "proper Christian customs". However, it is hard to understand how today church leaders can be lionised, who at the time denied legitimacy to those believers who were prepared to offer resistance.

2. Another factor seems to be responsible for the affinity between the churches and the Nazis, and therefore for the failure of the churches to oppose them. This is the Christian fondness for authority, especially when this authority is presented as guaranteeing the freedom of the church, and protecting morality, religious instruction, sectarian schools and the Christian family.

3. In addition to this there is the latent antisemitism of the churches. This appears not only in Luther, but is a constant theme in the two-thousand-year history of Christianity. This is true of the picture of the Jews transmitted by the Jewish apostle, Paul, who, according to the Israeli theologian Shalom Ben-Chorin, presents a picture of the Jews that is not only highly ambivalent, but in general antisemitic. The most antisemitic text of the New Testament is doubtless the Book of John. There Israel appears as the embodiment of evil: more than fifty times the Jews were called the enemies of Christ who continually sought to kill him. This perception of the Jews as the murderers of God, which was handed down in the Christian story of the Crucifixion through the centuries, has had dreadful effects up to the very recent past. Even in the texts of those Christians who rejected the persecution of the Jews, this historical prejudice can be seen at work.

4. Not only did the Christians as believers fail morally, but above all the churches as institutions did so, too. To a great extent they tried to suppress criticism of the most shocking incidents, because they saw themselves in many respects as in agreement with the Nazis. This is why very few in the Christian churches during the Third Reich found the courage to oppose the political terror of the state against the Jews and other nonconformists. As long as it was "only" literary figures, homosexuals, Jehovah's Witnesses, Communists, Jews and Gypsies, the Nazis were able to count on the — often well-wishing — acquiescence of the churches, and more than a few Christians.

5. It is true that on 14.03.1937 Pope Pius XI in his encyclical, With Burning Concern, had denounced many of the infringements of the rights of the Church, yet the attacks on human rights and freedoms, which were already visible, he addressed only in very general terms. This public statement, too, shows how much the Church hoped it might be able to reach an agreement with the criminals, after all. The encyclical used an abstract, theoretical language, full of praise for the Church, but it didn’t really identify the crimes of the Nazis as such. The outrages that were mentioned in concrete terms were crimes against the Church, its youth organisations and schools, against religious instruction, crosses in the classrooms and similar things. Not a word about the concentration camps, about concrete breaches of law or about torture and terror.

The bishops complained that no clergy were allowed access to the inmates of the concentration camps to administer the sacraments — but didn’t condemn the very existence of these instruments of terror and the brutality that reigned within their walls.

5. Open complicity

When Hitler invaded Austria, instead of protesting against the annexation of their country which violated international law, on 18.03.1938, a few days after the papal encyclical, the Austrian bishops gave way to jubilation, They "joyously recognised"

"that the National Socialist movement has performed and continues to perform outstanding accomplishments in the area of German ethnic and economic development, as well as in the social politics of the German nation and people, especially for the poorest classes. We are also convinced that through the actions of the National Socialist movement the danger of destructive, godless Bolshevism will be averted. The Bishops will accompany this action in the future with their best wishes and blessings and will also admonish the faithful in this respect. ... "

It would have been bad enough if this text from all the Austrian bishops had been made as a formal position paper to the aggressor without any further greetings. However, Cardinal Innitzer furnished this declaration with an obsequious accompanying letter to Gauleiter, Fritz Bürkel, in which he said:

"You can see from this that we bishops, of our own free will and without compulsion, have fulfilled our national duty. I know that this declaration will be followed by a successful collaboration. With the most respectful regards and Heil Hitler! Th. Cardinal Innitzer EB. "

Like almost all the bishops' public statements of those years, this text makes it clear that for those in the church hierarchy it was a matter of preserving their influence and the assets of their institution. This was made particularly clear in Innitzer’s clarification of their declaration three weeks afterwards, on 6.04.1938:

"The bishops demonstrate their opposition to breaking the laws of God, [and] of the freedom and rights of the Church. They demand the observance of the Concordat, the right to the religious education of young people, the banning of propaganda against the Church and respect for the right of Catholics to promulgate and practice their faith and the Christian gospel. "

People who were accustomed to believe their bishops were led by them into a national and worldwide calamity. For the Church hierarchy, it was not a matter of the people’s welfare, but solely of their own position and the maintenance of Church privilege.

This becomes uncontestably clear when one reads the obsequious way in which Cardinal Bertram congratulated Hitler on the occasion of his fifty-first birthday in April, 1940. Even then many Catholics were rendered speechless by this ecclesiastical presumption. Bertram wrote:

"A review of the incomparably great successes and events of recent years and the gravity of this war which has come over us gives me, as chairman of the Fuldaer Bishops' Conference, special reason, in the name of the bishops of all the dioceses in Germany, to convey to you on your birthday the warmest felicitations. This occurs in conjunction with the ardent prayers offered at the altar on the 20th of April that the Catholics are sending to Heaven for the German people, army and Fatherland, for the state and Führer. This is being done in deep consciousness of the national and religious duty of loyalty to the present state and its rulers, in the full sense of the Divine commandment that the Saviour Himself and the Apostles have handed down. [We] protest against the suspicion, nourished by anti-Church circles and secretly disseminated by them, that our declaration of loyalty is not fully dependable....

"I beg to be allowed to call to remembrance that our aims do not stand in any contradiction to the programme of the National Socialist party and that they find a clear echo in your own policy statement of 23.03.1933 and commitment of 28.04.1933. ...with the most reverend obedience, Cardinal Adolf Bertram, Archbishop of Breslau."

The Bishop of Berlin, Konrad Graf von Preysing was so incensed at this degrading, fully voluntary congratulation that he immediately resigned from the press council and wanted to tender his resignation as bishop.

Not much better than Bertram's performance was that of the Munich Cardinal Faulhaber, even though he has often been presented as one of the staunchest resistance fighters against the Nazis. He certainly always found very frank and sharp words whenever the Nazis encroached on the immediate interests of the Church. Yet even here, he always left out of his criticism the Führer, for whom he had a marked sympathy.

As thanksgiving for Hitler's escape from the assassination attempt of 9.11.1939 Faulhaber prescribed for the service in the Munich Church of Our Lady the hymn, "Mighty God we praise you". When he was interrogated by the Gestapo on 20.07.1944 about the plot to kill Hitler, because he was suspected of having had foreknowledge of it, Faulhaber stated in a protocol:

"I am shaken, because as bishop I must condemn and denounce before the whole world the crime of a murderous plan against a head of state." In the same protocol he described the attempted putsch as "such madness as would have thrown our people into the most fearful chaos and led to the victory of the most radical form of Bolshevism" and he didn't forget to mention that he had retained his veneration for the Führer since the long talk audience with him on 4.11.1936. In fact, every time there was resistance in Germany Faulhaber betrayed it in favour of a mass murderer and a criminal clique, apparently because he always hoped the Nazis would confer for benefits on the Church.

Even in the face of the murder of many thousands, justified as "the elimination of worthless beings", ("lebensunwertes Leben"), the bishops initially made only formal protests to the responsible state and federal authorities. Finally on 12.07.1941 — almost two years after the programme was begun — the bishops sent a memorandum to the federal government. However, all of this took place behind closed doors. The Catholic people heard nothing of this and were not meant to hear anything. It wasn't until late summer in 1941 that the Bishop von Galen in Münster revealed the murders in the hospitals and nursing homes of the State of Westfalen. At the same time he reported the offence to the State Attorney in Münster. However, no matter how much one may admire the fearlessness of this bishop, the question still remains as to why the Bishop — or, as would have been better, all the bishops together — didn't protest openly far earlier. Perhaps it would have saved the lives of several thousand people. As it was, the huge murder programme was almost completed when Hitler suddenly stopped it. It is true that the murders continued to a certain extent unofficially, but the formal ending of it by order of Hitler himself shows that public protest could indeed bring results. When the Jews were driven into the Holocaust in hundreds of thousands, no public word was uttered. The only protest was that among those being murdered were Jews who had been baptised.

Even in the face of the murder of many thousands, justified as "the elimination of worthless beings", ("lebensunwertes Leben"), the bishops initially made only formal protests to the responsible state and federal authorities. Finally on 12.07.1941 — almost two years after the programme was begun — the bishops sent a memorandum to the federal government. However, all of this took place behind closed doors. The Catholic people heard nothing of this and were not meant to hear anything. It wasn't until late summer in 1941 that the Bishop von Galen in Münster revealed the murders in the hospitals and nursing homes of the State of Westfalen. At the same time he reported the offence to the State Attorney in Münster. However, no matter how much one may admire the fearlessness of this bishop, the question still remains as to why the Bishop — or, as would have been better, all the bishops together — didn't protest openly far earlier. Perhaps it would have saved the lives of several thousand people. As it was, the huge murder programme was almost completed when Hitler suddenly stopped it. It is true that the murders continued to a certain extent unofficially, but the formal ending of it by order of Hitler himself shows that public protest could indeed bring results. When the Jews were driven into the Holocaust in hundreds of thousands, no public word was uttered. The only protest was that among those being murdered were Jews who had been baptised.

Anyone who offered resistance to the murderous regime, whether as politician, clergyman, monk or nun, ordinary Christian or simply as a German citizen, received no support from the official Church; in fact, as we have seen above, it was even possible for him to be accused by it of treason.

On 23.02.1946 Konrad Adenauer sent the Bonn pastor, Dr. Bernhard Custodis, a memorandum which is unfortunately not widely known. In it he comes to a clear and severe judgement against the behaviour of the churches. He ends his long account thus:

"If the bishops had all together on the same day taken a public position from the chancel, I believe they could have averted a great deal. That did not happen and for that there is no excuse. If this had resulted in the bishops landing in prison and in concentration camps, that would have done no harm [to their cause], quite the contrary. All that did not happen, and therefore it is best to hold one's peace."

And he continues, that if only there had at least been read out in the Catholic church services and in those of the Bekennende Kirche (Confessing Church), the Protestant movement that resisted the pro-Nazi theology of the Deutschkirche the names of persecuted clergy, as representatives of hundreds of thousands of others, clergy who had been displaced, driven out, arrested and forbidden to preach or give religious instruction. Adenauer was of the opinion that it was permissible to use liturgy for open protest against terror and lies. If this had happened, the state of ignorance of the faithful could have been replaced by a healthy concern which would have encouraged them to attempt to save those in peril of their lives. None of this happened, wrote Adenauer, and therefore it is best to hold one's peace.

If one is of this opinion, then today one should not depict the collaborative silence of the institutional churches in that terrible time as "resistance" and thereby falsify the record. Yet the impression of a clear antagonism between church and state which emerges from the last years of the war is carefully fostered. It wasn't until the Nazis neared defeat on the battlefield that the churches changed sides. They began to protest — only now and again and not very loudly — but at least they finally said something.

James Parkes, concludes that

"Individual Christians did risk their lives and acted to save Hitler's victims — but with the churches the line has remained as it was, uninterrupted by either sufficient admission of guilt or by a common resolve to restitution or remorse. "

It's hard to add anything to the verdict of this Church of England priest.

6. The churches' self-portrait after 1945

With the defeat of the Nazis, the German Reich with its complete infrastructure collapsed, leaving only the two large churches with their practically undamaged organisational structure. All the other organisations, the political parties, the freethinkers' organisations and the unions had been forbidden and broken up. Other organisations, including the public service, had been compromised through the behaviour of their members in the Third Reich. They all had to start over and reorganise under the supervision of the occupying forces. Only the churches had retained an intact infrastructure - with a branch in every village. The churches felt themselves to be on the side of the victors, and they were regarded as such, by both the Allies and the populace. In fact, some even called the Vatican, "the fifth occupying power".

The churches were therefore able to establish a formidable presence in the German states that were reconstituting themselves, and secure remarkable political influence. The churches and their representatives, above all the bishops, were treated in a blanket fashion as if they had all been victims of the Nazis, without any check on the behaviour of individuals. Notorious Nazi sympathisers in the ranks of the clerics were treated as malign mavericks and withdrawn from public functions. Forgotten during these decisive months was the benevolent attitude of many bishops, priests, pastors and leading lay members, who had regarded the Nazis as a bulwark of the German-Christian people and as a spearhead against the culturally destructive forces of Bolshevism, Socialism and "Jewish" Liberalism. The late and courageous words of a few bishops were used to try to prove that church resistance to the Nazis had been general and total — even though these protests were almost exclusively directed against the takeover of cloisters, the breach of Hitler’s Concordat with the Pope or the euthanasia of the mentally ill (Christians). In other words they served primarily to preserve the interests of the Church. What was in general a very cautious distancing of the Church from National Socialism was — and continues to be — blown up into a battle between "cross and swastika", God and Satan, good and evil.

At a time when it was very hard to obtain paper for German publications, the Munich suffragan bishop, Johann Neuhäusler was able to publish as early as the spring of 1946 his book, The Cross and the Swastika: the Battle of National Socialism against the Catholic Church and the Church Resistance. This two-volume 824-page work founded the legend of church resistance during the Third Reich.

That the churches were subject to chicanery and partial attacks cannot and should not be denied. However, much that was tolerated by other groups as a natural setback was interpreted by the churches, when it happened to them, as "persecution of Christians". The churches' self-pity is all the more strange when one remembers the tolerant restraint shown by the churches as Communists, Socialists, freethinkers and democrats were persecuted, and Jews and Gypsies were gassed as "vermin".

A typical example of such "selective memory" is the so-called "banning of crosses in the classroom". Recently this figured again and again in the vituperation against the ruling of the highest German court (of 16.05.1996) that crosses in schools were unconstitutional. In actual fact, under the Nazis there was no nation-wide action against crosses in schools, only a few local rulings: Oldenburg in November, 1936, Bislich and Frankenholz in February, 1937, and Affecking in September, 1937. In all these cases, the local encroachments on Church privilege were called off by "higher authorities".

Above all it was in the realm of legal privileges that the churches stood firm. Beginning in 1945, the churches insisted on the continuation of the concordats and church treaties with the individual German states and on the Reichskonkordat which had been signed with the Nazis in 1933. The postwar governments that were being formed in the Germans states and municipalities were careful not to encroach on these loudly proclaimed church prerogatives. This was even so for those governments that traditionally distanced themselves from the churches. They didn't want to - and, in fact, couldn't afford to - let themselves be suspected of continuing the Nazis' "persecution of the churches". In addition, the occupying forces saw in the churches their most important allies, who could help deliver social services to the populace and who could also be useful for "de-Nazification".

7. Instead of acknowledging their share of blame, the churches demand new privileges

One searches in vain in the official bulletins of the German churches in the months after the war for honest assessments. It is appalling how little thought was devoted to the question as to how and why it came to the catastrophe of National Socialism and military defeat. When this question was addressed at all, it was only to bemoan that everyone had had to suffer because of the actions of a few godless people who hadn't followed the teachings of the Church. The national political catastrophe was immediately reinterpreted to show what happens when the teachings and the freedom of the church aren't sufficiently respected. In the light of the Holocaust one would have expected from the churches a clear and concrete admission of guilt for their share in it, or at least for their silence about the persecution and murder of the Jews.

Instead, we hear immediately in 1945 the absolute demand for a privileged public position for the churches, for the precedence of sectarian schools and for proper respect towards the churches. Anything else would be a relapse into godlessness and National Socialism.

During the whole Nazi period religious education in the schools was never forbidden, but on the contrary was generously encouraged. Despite this, after the war the churches demanded, more or less as compensation, that there must be Catholic schools and religion classes, so that "something like that" never happened again. In fact, however, one has to ask oneself if the religion classes before and during the Nazi period didn't contribute substantially to Christian support for the war as the "work of God", through their inculcation of the doctrine of "obedience to the authorities". On 26.04.1933 Hitler told the Catholic Bishop Berning, "Religious soldiers are the most valuable ones. They do their utmost. Therefore we will retain the sectarian schools.... "

The churches were quietly complicit at a time when they could still have spoken out; that is what they have to answer for. That they later kept silent due to fear is something that today no one should blame them for, yet this in itself makes it clear that as institutions they were no better than anyone else. Like so many others in the Nazi period, the churches went with the current. They didn't promote peace or call for justice and they certainly didn't set any standard for moral behaviour. On the contrary, with their directives about the authority sanctioned by God they soothed the troubled consciences of many Germans, and indeed they discredited and often criminalised the voice of individual conscience. The churches were petty and more guilty than others who acted similarly because they led people astray by appealing to the commandments of God. They have been mirrors of their society, but in no way models of moral behaviour. During the Nazi period - and also now - they have generally only preached what fitted in with the times - or with their own interests.

See also:

♦ Gregory S. Paul, The Great Scandal: Christianity’s Role in the Rise of the Nazis, Part 1, Part 2 and Part 3

♦ Pius XII, concordat negotiator and Holocaust pope

This is a gateway to more than a dozen online articles about the connections between Hitler, Pius XII and the concordat.

Source:

Johannes Neumann,

(professor for the sociology of law and the sociology of religion,

University of Tübingen, Germany)

"Die Kirchen in Deutschland,1945: Vorher und nachher,

Versuch einer Bilanz".

First delivered as a lecture at the University of Tübingen in 1995,

the full-length German original — with footnotes — can be found at

http://www.ibka.org/artikel/ag98/1945.html

Translated and edited by Muriel Fraser, with the kind permission of Dr. Neumann.

The Nazis and the German churches

The Nazis and the German churches